Justification for Closing the Separate Unit

I am writing today to advocate for the closure of our separate unit for students with physical, sensory, intellectual, developmental, and socioemotional impairments. I have taken this position fundamentally because our current segregated system is outdated and unethical. This has been highlighted by the addition of a new family enrolling their children—Eliana in Year 11, and twins Georgio and Luca in Year 8—where Luca's Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) would currently result in segregation from his sibling. Such practices undermine inclusive education principles. Closing the unit aligns with human rights, social justice, and relevant Australian and Victorian policies.

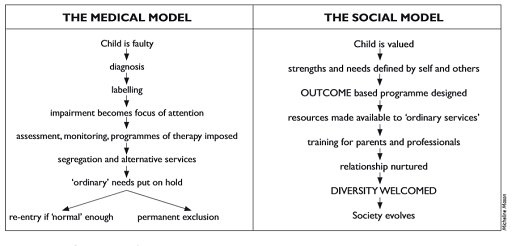

For too long, the practice of placing students with disabilities in separate ‘units’ has been accepted. This historical approach was fundamentally driven by the outdated medical model of disability, which views Luca’s impairment (ASD) as an inherent deficit that necessitates separation and specialised instruction away from the mainstream. However, Australia’s commitment to human rights and equitable access has driven a major evolution in how education is delivered. We are moving away from the segregationist practices of the past toward genuine inclusion, a shift that is required for systemic transformation. This modern imperative is grounded in the social model of disability, which correctly identifies that the barriers to equitable access and participation are not located within Luca, but rather within rigid school environments and societal structures. By closing segregated units and redirecting resources to enhance mainstream capacity, we uphold the non-discriminatory rights mandated by the UN, ensuring every student thrives alongside their peers

Human Rights Perspective:

Article 24 of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) mandates Australia to ensure an inclusive education system at all levels, rejecting segregated settings as incompatible with non-discriminatory education rights (United Nations, 2006). Segregated units perpetuate exclusion, denying students with disabilities equal participation and social integration opportunities (Anderson & Boyle, 2019). General Comment No. 4 calls for systemic transformation to eliminate barriers, emphasizing the need to phase out segregated units to uphold learner dignity and rights (United Nations, 2016).

Social Justice Principles:

Segregation is inherently unequal and discriminatory, reinforcing societal stigma and limiting equitable opportunities (Carrington et al., 2020). The social model of disability attributes barriers to environmental failures, not individual impairments, aligning with equity and inclusion ideals (Humphrey & Symes, 2013). Separate units suggest students with disabilities do not belong in mainstream settings, increasing isolation and hindering positive community attitudes toward diversity (Lilley, 2013). Inclusive education fosters empathy, reduces prejudice, and promotes social cohesion, normalizing disability as human variation for the benefit of all students (Saggers et al., 2016).

Policy and Framework Support:

Victoria’s Students with Disability Policy commits to inclusion, emphasizing non-discrimination and respect for diversity (Department of Education and Training, Victoria, 2023). The Disability Inclusion program, fully implemented by 2025 with $1.6 billion and an additional $237.3 million in 2025–26, introduces strengths-based Disability Inclusion Profiles and SHARE principles (Department of Education, Victoria, 2024). These reforms replace segregated models like the Program for Students with Disabilities, enabling tailored supports within mainstream schools (Commonwealth of Australia, 2005).

Closing the unit would redirect resources to enhance mainstream capacity.

Resources such as teacher training, assistive technologies, and in-class support officers, leading to improved academic, social, and employment outcomes for students with disabilities (Webster & de Boer, 2021). Evidence from the 2023 Royal Commission underscores that segregation perpetuates lifelong disadvantage, urging reforms for full compliance with the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (Royal Commission into Violence, Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation of People with Disability, 2023). By embracing inclusion, our school can model equity, ensuring every student, like Luca, thrives alongside peers. I urge colleagues to support this transition for a just, rights-based education system.

By embracing inclusion, our school can model equity, ensuring every student, like Luca, thrives alongside peers. I urge colleagues to support this transition for a just, rights-based education system.

References

Anderson, J., & Boyle, C. (2019). Looking in the mirror: Reflecting on 25 years of inclusive education in Australia. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 23(7-8), 796–810. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2019.1622802

Carrington, S., Saggers, B., Webster, A., Harper-Hill, K., & Nickerson, J. (2020). What universal design for learning principles, guidelines, and checkpoints are evident in educators’ descriptions of their practice when supporting students on the autism spectrum? International Journal of Educational Research, 102, 101598. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2020.101598

Commonwealth of Australia. (2005). Disability Standards for Education 2005. https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/F2005L00767

Department of Education and Training, Victoria. (2023). Students with disability policy. https://www2.education.vic.gov.au/pal/students-disability/policy

Department of Education, Victoria. (2024). Disability inclusion: Overview. https://www2.education.vic.gov.au/pal/disability-inclusion/overview

Humphrey, N., & Symes, W. (2013). Inclusive education for pupils with autistic spectrum disorders in secondary mainstream schools: Teacher attitudes, experience and knowledge. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 17(1), 32–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2011.580462

Lilley, R. (2013). The Mo(ve)ment to inclusive education in Australia: Mothers of children with disabilities speak out. Disability & Society, 28(6), 811–824. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2012.763191

Royal Commission into Violence, Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation of People with Disability. (2023). Final report: Volume 7 – Inclusive education, employment and housing. https://disability.royalcommission.gov.au/publications/final-report-volume-7-inclusive-education-employment-and-housing

Saggers, B., Klug, D., Harper-Hill, K., Ashburner, J., Costley, D., Clark, T., Bruck, S., Trembath, D., Webster, A. A., & Carrington, S. (2016). Australian autism educational needs analysis: What are the needs of schools, parents and students on the autism spectrum? Cooperative Research Centre for Living with Autism. https://www.autismcrc.com.au/knowledge-centre/resource/australian-autism-educational-needs-analysis

United Nations. (2006). Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities.html

United Nations. (2016). General comment No. 4: Article 24: Right to inclusive education. https://www.ohchr.org/en/documents/general-comments-and-recommendations/general-comment-no-4-article-24-right-inclusive

Webster, A. A., & de Boer, A. (2021). Preparing teachers for inclusive education: A comparative analysis of teacher education in Australia and the Netherlands. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 25(12), 1410–1426. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2019.1611239